Researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) have learned a lot about Monterey Bay using robotic submersibles to look deep below the bay’s surface. Now they can listen to the bay as well, using an ultra-sensitive underwater microphone. Sounds recorded by this hydrophone have already provided surprising information, including evidence that beaked whales, though rarely seen, are common in the outer bay.

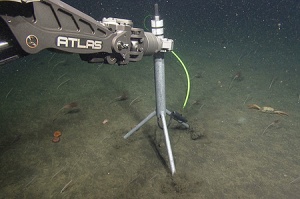

In July 2015, MBARI researchers installed a broadband hydrophone on Smooth Ridge, about 30 kilometers (18 miles) from shore and 900 meters (3,000 feet) below the sea surface. Since that time, signals from the hydrophone have been relayed back to shore in real time, 24 hours a day, using MBARI’s cabled ocean observatory, the Monterey Accelerated Research System (MARS).

The new hydrophone doesn’t look very impressive. It’s just a metal cylinder about two inches in diameter, mounted on a metal tripod on the muddy seafloor. But it is extremely sensitive and can pick up a vast range of sounds, including those too low and too high for humans to hear.

A spectrum of sound

“We’re trying to characterize the soundscape of Monterey Bay,” says John Ryan, the biological oceanographer in charge of the project. “This means looking at the whole spectrum of sounds that we record and identifying all of the phenomena they represent. This includes biological sounds such as vocalizations of marine mammals, the sounds of physical processes such as wind and rain, and the sounds of human activities.”

Most adults (at least those who haven’t attended too many rock concerts) can hear sounds from about 20 Hertz (the low rumble of an earthquake) up to 16,000 Hertz (the high-pitched buzzing of a mosquito). The new hydrophone can pick up sounds ranging from 10 Hertz to 128,000 Hertz.

During a recent meeting with underwater acoustics experts, Ryan played a few of the distinctive sounds recorded with the hydrophone.

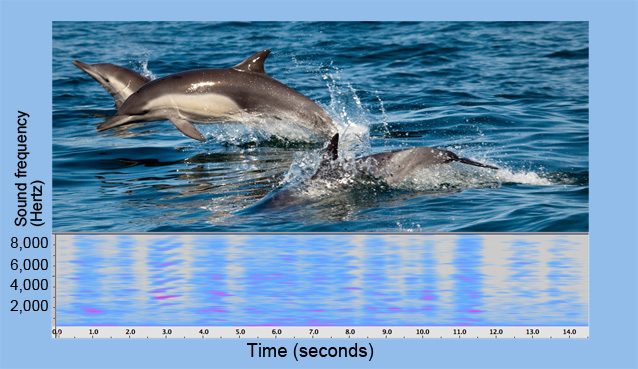

Here’s a recording of dolphins:

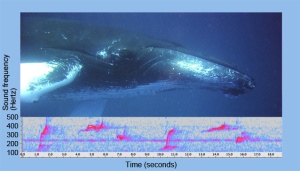

And here’s one of humpbacks:

The first were low-frequency sounds that resembled a semi-truck downshifting. Ryan explained that these were the calls of blue whales. At about 10 Hertz, these calls are only audible when “sped up” by computer software and played through subwoofer speakers.

Next he played a series of high-pitched whistles and clicks. The experts speculated these were from common dolphins and Risso’s dolphins, respectively. These animals can make (and presumably detect) sounds as high as 60,000 Hertz.

Cocktail party chatter

Ryan then played a high-pitched sound that resembled a person rubbing a balloon, but none of the experts could begin to guess what made that noise. Ryan also played a recording of what sounded like sea lions barking underwater. In some clips, the calls of different animals overlapped like the chatter of voices at a cocktail party.

For Ryan, picking out a few clips to play at a meeting was relatively easy. The bigger challenge: analyzing the ongoing deluge of data from the hydrophone—about two terabytes a month.

“Our current approach is to turn the sound into a picture called a ‘spectrogram,’” he says. “This allows researchers to visually browse through the soundscape to look for unusual events, as well as for repeating patterns such as daily cycles in activity. Acoustics experts can also use spectrograms to figure out what’s making certain sounds, including what kinds of animals are present.”

Turning to AI

But human experts don’t have time to analyze all the data. So MBARI Software Engineer Danelle Cline is training computers to do the job. As Ryan explains, “We’re working on getting computers to recognize the vocalizations of different species of marine mammals. We’re hoping to use artificial intelligence software to do this.”

Right now, Cline is testing and expanding a program originally developed by MBARI summer intern Prateek Murgai. The software can identify a few very distinctive calls, such as the deep rumbles of blue whales, but it doesn’t work as well for others—especially when there’s a lot of background noise.

By far the loudest sounds recorded by the hydrophone thus far are from passing boats and ships. Researchers have analyzed brief sound clips from the hydrophone to identify the sounds of individual boats and ships. For example, on December 30, 2015, a supermassive container ship sailed northward past Monterey Bay, on its way to San Francisco Bay. An analysis by marine acoustician Mark Fischer found that the hydrophone picked up extremely low-frequency (one to 10 Hertz) sounds from this ship for almost 11 hours. The sounds were first detected when the ship rounded Point Sur, about 70 kilometers (42 miles) south of the bay, and continued until the ship approached the Golden Gate, about 125 kilometers (80 miles) to the north.

Another unexpected finding was that calls of rarely seen Baird’s and Cuvier’s beaked whales were much more frequent than anyone expected. These whales spend most of their time diving in deep water and are almost never seen at the surface, so very little is known about them.

To share his exciting hydrophone discoveries with students and the general public, Ryan worked with MBARI engineers to design a mobile sound system that can play back some of the sounds it’s recorded. Ryan and Cline are also developing a web page where anyone can browse through spectrograms from the hydrophone, listen to some of the sounds that have been recorded, and (eventually) hear recordings from the hydrophone in near-real time.

Ryan is enthusiastic about the potential of the new hydrophone.

“We’re still in the process of demonstrating what’s possible with this new instrument, both for research and education,” he says. “So far we’ve only had time to look at a few snippets of sound. And yet each one has had something wonderful in it. That speaks to the potential of the greater data set.”

a great article

LikeLike

I really think it’s great to be able to listen to what’s going on in the sea. I can imagine the BEAUTIFUL whale sounds that must be heard. I use to have a cassette tape called whale songs but I wore it out listening to it so much. They sounds they make really put your mind and you at peace.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Her Headache and commented:

A job working listening to marine animal sounds would have been cool. There’s nothing else quite like it.

LikeLike